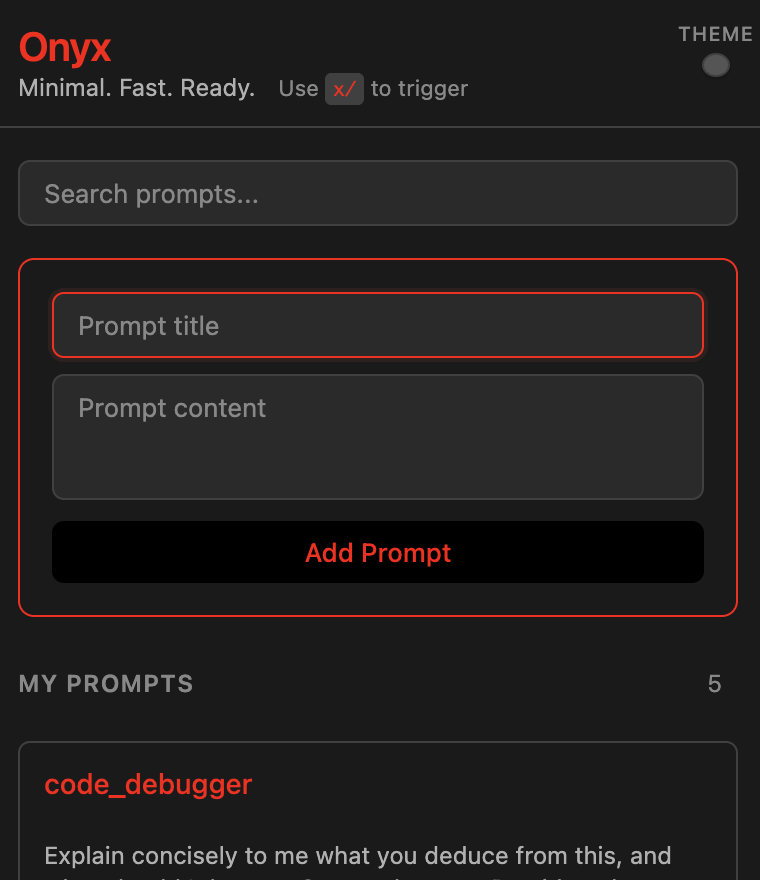

Onyx

Bridging the gap between prompts and productivity with a local-first browser extension

- Browser-Native Architecture

- Local-First Architecture

- Input handling and Interaction Design

- Productization and Launch

Onyx is a lightweight browser extension for saving and inserting reusable prompt snippets. It was built with a local-first mindset to eliminate backend complexity and protect user data. The design prioritizes speed and simplicity over feature bloat. It integrates with Chrome's popup interface and handles snippet persistence reliably. The extension is live and usable across websites and text fields.

- Quickly save and recall prompt snippets anywhere in the browser

- Minimal UI that stays out of the way

- Works fully offline/local — no cloud storage required

- Fast insert into text fields with a popup and hotkeys

- Simple add/edit/delete snippet management

- Published on Chrome Web Store with low friction install

01.

Architecture

Local-first removes friction

We chose a local-first architecture. Not because it was trendy, but because it eliminated entire classes of problems before they appeared.

All snippet data lives in the browser. There is no account system, no backend, and no synchronization service to build or maintain. Installation is the onboarding flow. Users can create and insert their first prompt immediately.

This choice had several practical effects. The extension works offline. It works behind corporate firewalls. It works in environments where outbound requests are restricted. There is nothing to configure and nothing to break.

Operationally, this removed ongoing cost and complexity. No servers to host. No databases to secure. No compliance reviews. No on-call rotation. Chrome's built-in storage handles persistence and optional cross-device sync without any additional code.

Privacy follows naturally. Prompts never leave the user's machine. We did not need to promise security or explain encryption. We could state a simpler fact: the data stays in the browser.

The trade-off is obvious. There is no real-time collaboration or shared libraries. For a single-user prompt tool, this was acceptable. The reduction in friction outweighed the loss of features.

02.

User Experience

Small, focused UX matters

The goal was not to build a rich interface. The goal was to stay out of the way.

The popup loads in under 50 milliseconds. It consists of a single JavaScript bundle with no external dependencies, fonts, or trackers. By the time the browser registers a paint, the interface is already visible.

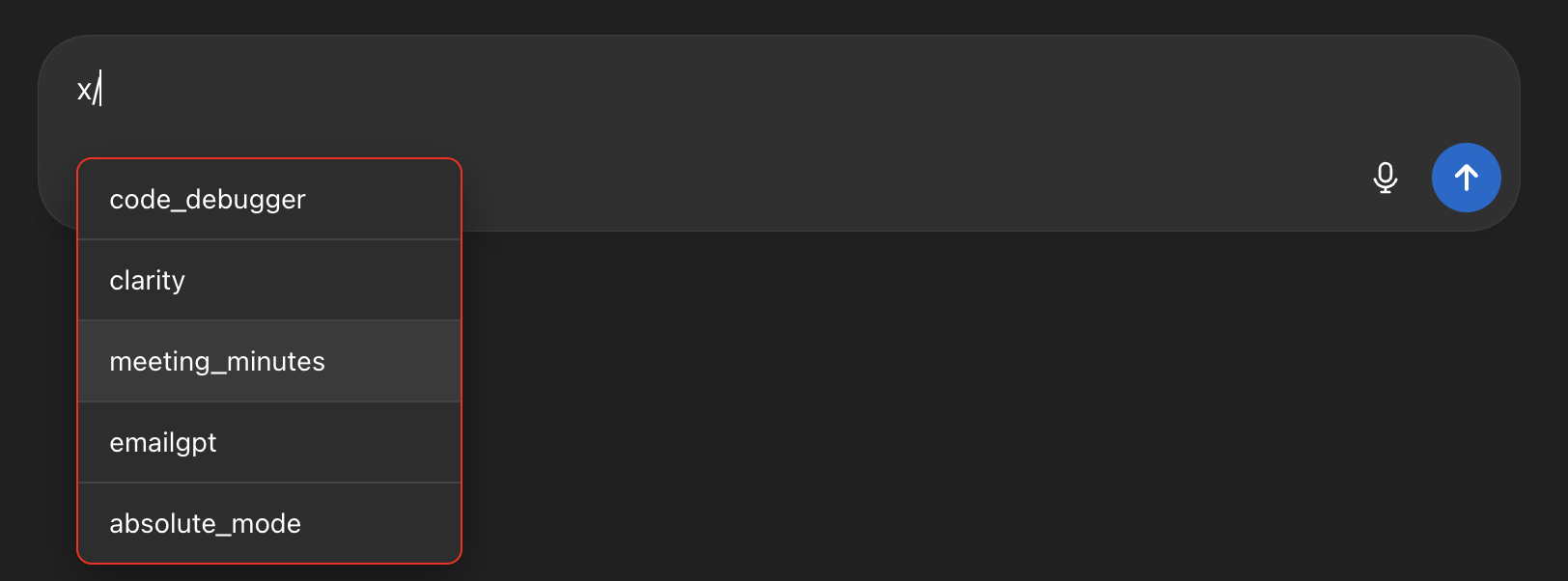

Interaction is keyboard-first. Typing x/ opens the picker at the cursor. Arrow keys move selection. Enter confirms. Escape dismisses. The mouse is optional, not required.

The UI surface area is intentionally small. The popup shows only two things: a form to add or edit a snippet, and a list of existing snippets. The options page mirrors the same interface at a larger size. There are no tabs, no settings pages, and no secondary flows.

Actions are designed to be reversible. Edit mode is clearly marked and can be canceled. Delete actions are hidden until hover and will support undo. Users should never wonder whether they lost data.

In testing, most users created their first snippet in under twenty seconds and inserted it into a chat in under ten. Several forgot the extension was running at all. That invisibility was the success metric.

03.

Technical Constraints

Respect host constraints, design fallbacks

We assumed that pressing Enter would confirm a selection everywhere. This assumption was wrong.

On Claude.ai, the input element intercepts Enter at a lower level and immediately sends the message. We tried several approaches: intercepting the event during bubbling, during capture, attaching listeners to shadow DOM roots, and re-binding handlers on re-renders. None were reliable.

| Attempt | Technique | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Bubble-phase listener | document.addEventListener('keydown', …) | Fires after Claude's React handler; message already sent. |

| Capture-phase listener | Same call with useCapture = true, plus e.stopImmediatePropagation() | Claude still sees the event—its input sits in a shadow DOM with its own capture listeners that run first. |

| Shadow-DOM retargeting | Attach listener to shadowRoot.host | Claude re-creates the host node on every render; listener is lost. |

The cost of failure was high. If interception failed even once, the user would accidentally send a message. That kind of error is visible, frustrating, and difficult to explain.

Rather than fight the platform, we added fallbacks.

Shift + Enter works consistently because Claude treats it as "insert newline," not "send message." Tab also works naturally as a selection key and is never mapped to sending. On sites that allow Enter to be intercepted safely, Enter behaves as expected. On Claude, it does not.

The final behavior is simple:

- When the picker is open, Shift + Enter and Tab always confirm.

- Enter confirms everywhere except Claude.

- When the picker is closed, the page behaves normally.

Accepting one extra keystroke on a single site produced a solution that is predictable, stable, and resilient to future changes. What began as an input-handling limitation became a small but deliberate UX decision.